J is for Japanese Missionaries #AtoZChallenge

The A to Z Challenge asks bloggers to post 26 posts, one for each letter of the English alphabet, in April. Most of us choose to make these posts on a particular theme. My theme for 2022 is Codebreaking in World War II, which fits with the topic of the novel that I’m writing. Visit every day (except Sunday) in April for a new post on my topic.

The A to Z Challenge asks bloggers to post 26 posts, one for each letter of the English alphabet, in April. Most of us choose to make these posts on a particular theme. My theme for 2022 is Codebreaking in World War II, which fits with the topic of the novel that I’m writing. Visit every day (except Sunday) in April for a new post on my topic.

J is for Japanese Missionaries

Any code-breaking operation that involves cryptanalysis of messages in different languages will need translators. The greatest unfulfilled need at the beginning of World War II was for Americans who spoke Japanese.

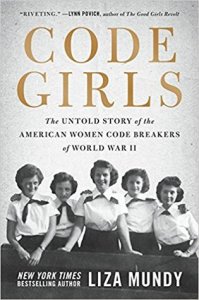

From Code Girls by Liza Mundy:

The language unit at Arlington was an exalted group of individuals who knew Japanese and could translate messages into English. This was an unusual skill for an American in the 1940s to have. Some translators were young officers—the j-boys—who had been sent by the Army to language training in Berkeley, California, and Boulder, Colorado. Others were scholars such as Edwin Reischauer. Others were missionaries who had lived in Japan. Many in the last two categories had learned the Japanese language out of interest in, and love for, the land and culture. Most felt an emotional attachment to the country and knew people who lived and worked there. They were now working to defeat the nation they once had proselytized and studied. (p. 324)

Earlier in the book, Mundy mentions BIJs – born-in-Japans. These people were generally the offspring of missionaries in Japan whose families returned home at the beginning of the war.

All of this made me curious about whether any Japanese Americans worked in the Navy or Army codebreaking units during World War II. I found this article on the National WWII Museum website that describes the work of Japanese Americans as translators and interrogators. It included this tidbit related to codebreaking:

Recognizing a weakness and hoping to exploit the American unfamiliarity with the Japanese language, Japanese communications were often transmitted in plain language rather than code.

I found no evidence of Japanese Americans working in cryptanalysis, however.

Code Girls told the story of one former missionary who had a vital role in the work at Arlington Hall. Virginia Dare Aderholdt worked on decoding messages in a system that the Americans called JAH – an all-purpose code that the Japanese used for low-security transmissions.

While many of Arlington Hall’s language units were headed up by j-boys, JAH was handled by a woman named Virginia Dare Aderholdt. According to a memo, Aderholdt graduated from Bethany College in West Virginia…which was a four-year college founded by the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), and offered a first-rate language department and a commitment to good causes. Many graduates did missionary work abroad. Virginia Aderholdt had spent four years in Japan and the JAH code now was her baby. She owned that code. She knew it backward and forward. She could scan and decode and translate almost simultaneously as it was coming through the machine built to receive it. (p. 326)

That skill came in handy on the day that Japan surrendered. Aderholdt decoded and translated the message, surrounded by coworkers who were anxious to be among the first to know that World War II was at an end. The message was sent from Tokyo to the Japanese ambassador in Switzerland who would convey it to the Swiss foreign office to relay to Allied leaders. “The message had to pass through two transmitting stations to Switzerland. The Americans snatched if from the first and worked so fast that Arlington Hall had it decoded before the Japanese received it on the other end.” (p. 329)

This was a fascinating read and I’m going to try and get a copy of Code Girls, I love my history books.

That’s amazing that the Japanese figured just plain Japanese was enough of a code for some stuff! Just goes to show how important it is to know multiple languages (not that I know Japanese.)

J is for Jewelled

It would have been so much easier to have Japanese Americans work on it… if they had not been sent away to camps. Go figure…

The Multicolored Diary